ARTOIS - Vimy Ridge

Year of visit: 2005, 2008

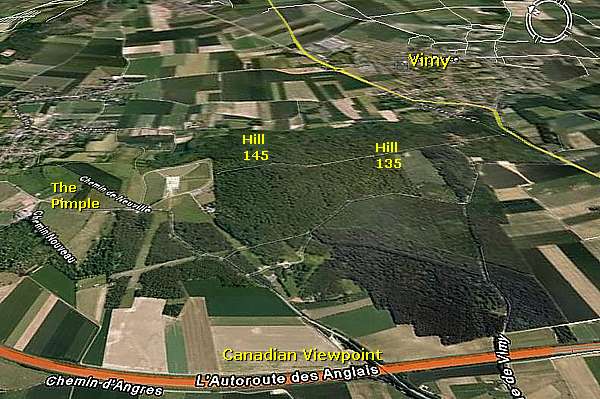

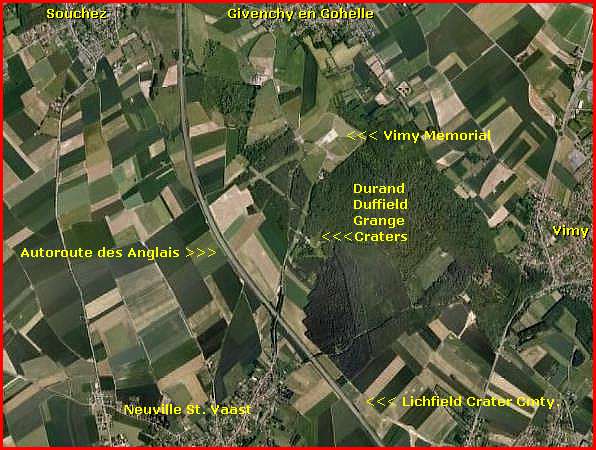

Between Lens and Arras, along the A 26, the "Autoroute des Anglais" lies Vimy Ridge, centre point of the Battle of Arras, 9 - 12 April 1917. We finish this photo impression about Vimy Ridge at the Lichfield Crater Cemetery.

During the Second Battle of Artois (9-15 May 1915), the French 1st Moroccan Division managed to take possession of the ridge, after an astonishing 4 km advance, but the Division was unable to maintain the ridge, due to a lack of reinforcements, and consequently suffered heavy losses.

The French suffered approximately 150.000 casualties in their attempts to gain control of Vimy Ridge and surrounding territory. Following the Third Battle of Artois (or for the British the Battle of Loos (September 1915)) the Vimy sector became calm for a period of time.

As on other former battlefields, on Vimy Ridge the fields are still full of unexploded explosives.

Visitors are warned not to walk outside the marked paths.

The hill and it's barren slopes provided little cover for attacking troops, ...

.. and it was an ideal position for machine guns and artillery to fire on enemy invaders.

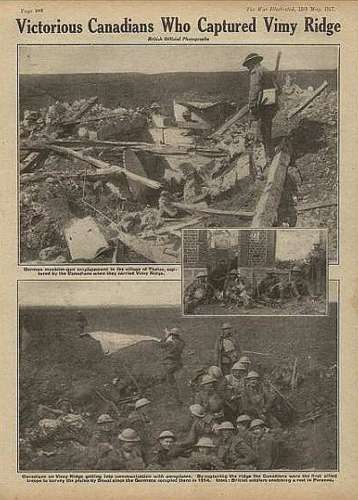

The Germans capture Vimy Ridge - 1914

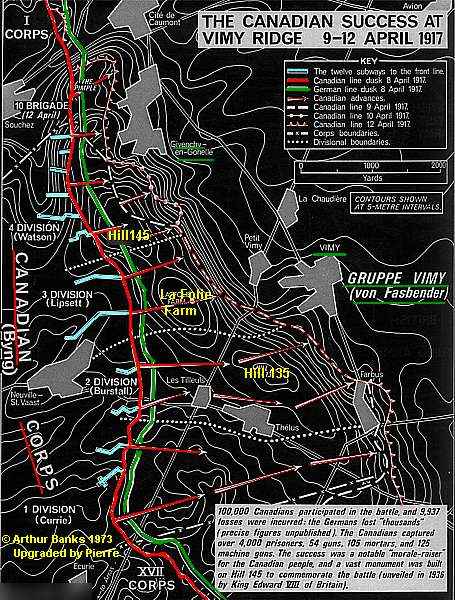

The Germans conquered Vimy Ridge in October 1914, during the First Battle of Artois. Situated 8 km northeast of Arras, the ridge is approximately 7 km in length with a height of 145 m. (Hill 145), providing a natural panorama view for tens of kilometers. The German Sixth Army had heavily fortified the ridge with tunnels, three rows of trenches behind barbed wire networks, artillery, and numerous machine gun nests to protect the Lens coal mines, which were essential to their war efforts.

Vimy Ridge was defended by the Gruppe Vimy, a formation under 1st Bavarian Army Corps Commander General Karl von Fasbender. A Division of Gruppe Souchez, under 8th Reserve Corps of General Georg Karl Wichura, was also involved in the front line defence along the most northern point of the Ridge: the Pimple.

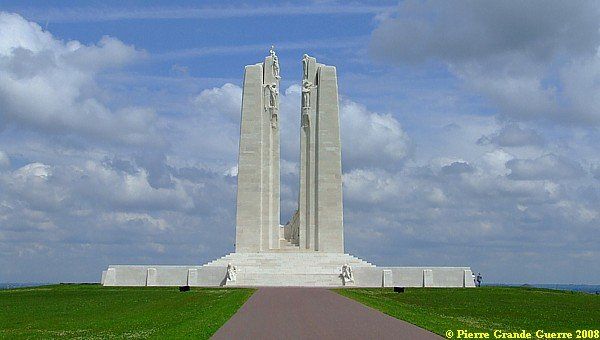

The Vimy Ridge Canadian National Memorial on Hill 145. In 2005 it was under construction of renovations.

In May 2008 we re-visited the renovated monument. Visit later also my Special Photo Impression about the Vimy Canadian National Memorial

.

For now two views of the renovated Memorial at Hill 145 of May 2008. Rear side, west.

Front, east side.

Traces of trenches and shell holes on the western slope of Hill 145.

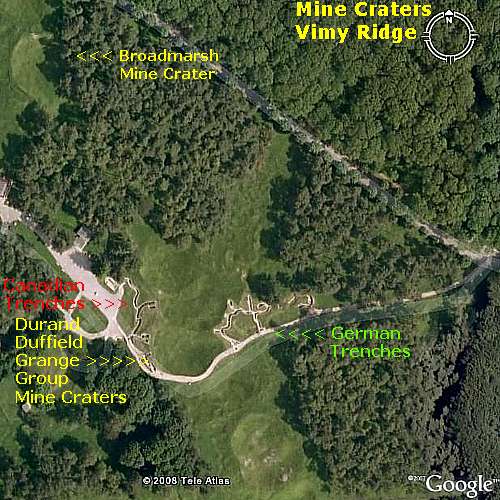

Twelve subways - thirteen mines

The Arras-Vimy sector was conducive to tunnel excavation owing to the soft, porous yet extremely stable nature of the chalk underground. As a result, an underground warfare had been an important feature of the Vimy sector since 1915, with no less than 19 distinct mine crater groups existing along the Canadian front by 1917. Since their arrival in 1916, British Royal Engineer Tunnelling Companies had been active with offensive mining against German miners with 5 Tunnelling Companies stationed along the Vimy front at the height of the operations.

In preparation for the assault, British

Tunnelling Companies, with the assistance of Canadian Engineers and

infantry, created extensive underground networks and fortifications.

Twelve subways, up to 1.2 km in length (the “Goodman” Subway), were

excavated at a depth of 10 meters. The subways connected reserve lines

to front lines, permitting soldiers to advance to the front quickly,

securely, and most important; unseen. Concealed light rail lines,

hospitals, command posts, water reservoirs, ammunition stores, mortar

posts, machine gun posts, and communication centres were also often

excavated in the subways. Many subways were also lit by electricity

provided by generators.

Thirteen mines were also laid under German positions, particularly near

the Pimple and the Broadmarsh Crater, with the intention of destroying

fortified points before to the assault.

We visit the preserved and restaurated trench system on Hill 145.

Before we go on: some concise information about the

Battle of Vimy Ridge (9 -12 April 1917)

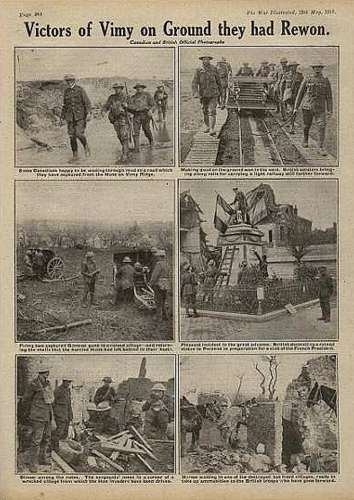

On 5 January 1917 General Byng was ordered to plan attacks for Vimy Ridge as the Canadian Corps objective for the Arras Offensive. A formal assault plan was adopted by early March 1917. For the first time, all four Canadian Divisions were to be assembled to operate in combat as one Corps. Four Canadian Divisions were joined by the British 5th Infantry Division, and reinforced by artillery, engineers, and labour units. This brought the Canadian Corps nominal strength up to 170,000 men of all ranks, of whom 97,184 were Canadians.

Allied commanders believed it impossible to capture the ridge. The Canadians had a plan. The ground assault had been planned meticulously. Full-scale replicas of the Vimy terrain were built to rehearse. Five kilometres of subterranean tunnels and subways were dug in order to move Canadian troops and ammunition up to the front without their being seen by German observers.

On 2 April 1917, an artillery bombardment of 7 days ahead with 2.800 guns was stepped up to wear down the German soldiers. Before the battle began, more than one million shells had been fired into German trenches.

In the morning of 9 April, Eastern Monday, at 5.30 AM, 20.000 Canadian soldiers attacked in the first wave of fighting in the battle of Vimy Ridge behind an creeping barrage of artillery fire. The Canadians were extremely fast and successful and took the ridge by afternoon.

The Germans were rather surprised. The did expect an attack. But they presumed the start of the large offensive would take another 2 or 3 weeks.

In the next 4 days the Canadian Corps achieved all of it’s objectives. In 4 days, there were 10.602 Canadian casualties, of which 3.598 Canadian soldiers died. The German forces suffered even more heavily: 20.000 casualties. But the ridge was taken, much of it in the first day.

We visit the trenches, which the Canadian Ministry of Veteran Affairs preserves along the Grange Group Mine Craters southeast of the Memorial.

We start at the Canadian 1st Line.

Not many words from here now. Let the photo's tell their own story.

Armoured plate with a rifle hole.

View at the Grange Group Mine Craters from the Canadian Parapet.

View at the German line on the other side of the crater lip.

Notice the German pillbox on the right for later.

View at the mine crater group.

We go around the crater lip to the German Lines.

The German 1st Line.

View from the German 1st Line over the craters to the Canadian 1st line.

Zig-zagging German trenches.

This looks like a relic of a German 17 cm trench mortar.

German machine gun pillbox.

West of the German lines: traces of trenches, shell holes, and mine craters.

From Vimy Ridge we continue a few kilometres southward to the southern foot of the ridge, to the

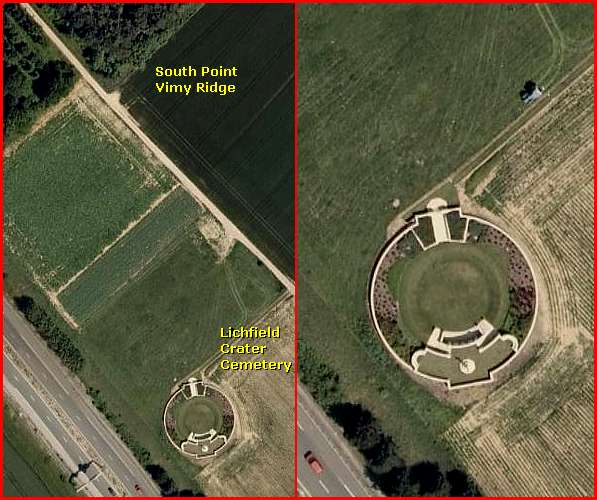

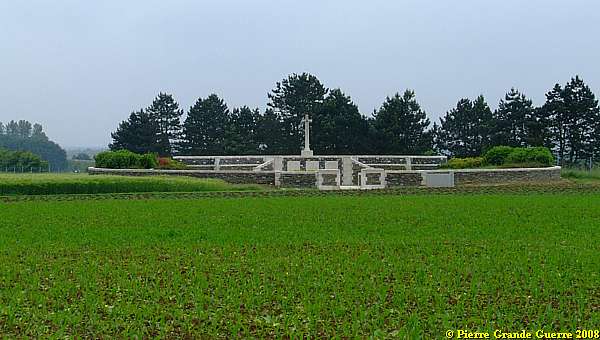

Lichfield Crater Cemetery

The Lichfield Crater lies near the most southern point of Vimy Ridge, along the Autoroute des Anglais.

A tunnel subway with a length of around 500 meters, running from west to east, lead to the Lichfield Mine , which has been blown on 9 April 1917 under the German "Volker" trench network. The diameter of the Crater is 35 meter.

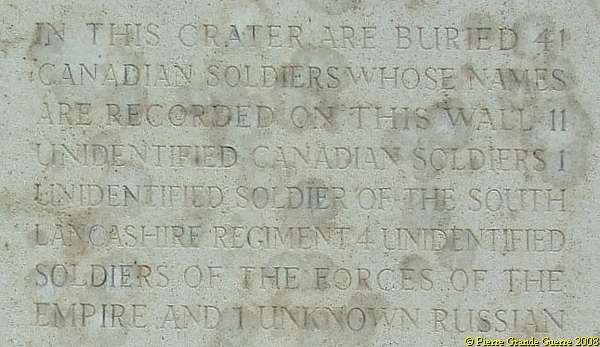

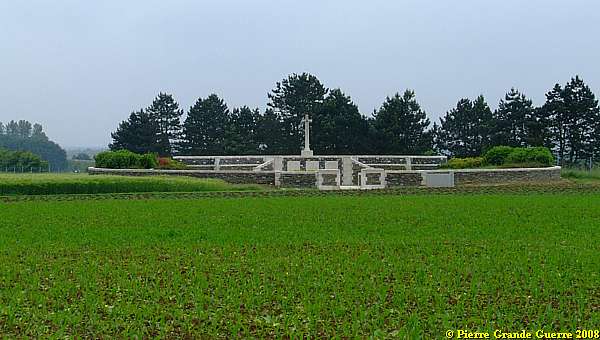

Nowadays the Lichfield Crater is a War Cemetery, a mass grave for Canadian soldiers and officers, fallen during the period of 9 and 10 April 1917.

The most southern point of the wood at the foot of Vimy Ridge is also still dangerous terrain.

Before we enter the footpath to the Cemetery we detect a rusted shell.

Lichfield Crater Cemetery

The Lichfield Crater was one of two mine craters (the other being Zivy Crater), which were used by the Canadian Corps Burial Officer in 1917 for the burial of bodies found on the Vimy battlefield.

The numerous groups of graves, made about this time by the Canadians, were not named as a rule, but serially lettered and numbered; the original name for Lichfield Crater was CB 2 A.

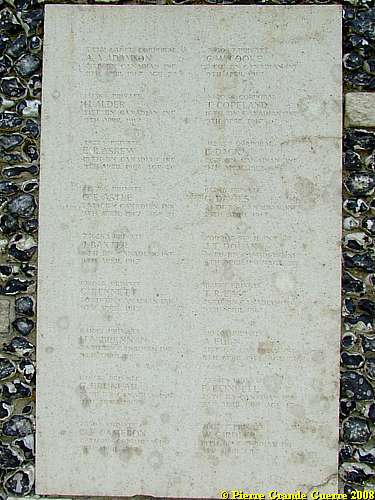

The crater is essentially a mass graves and

contains 57 First World War burials, 15 of them unidentified. All of

the men buried here died on 9 or 10 April 1917 with one exception, a

soldier who died in April 1916, whose grave was found on the edge of

the crater after the Armistice and is the only one marked by a

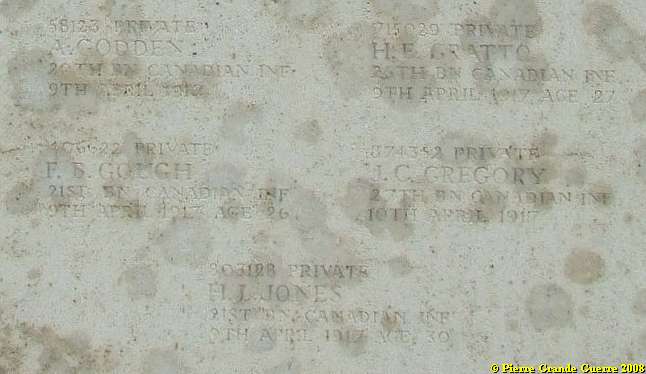

headstone. The names of the rest of those buried in the crater are

inscribed on panels fixed to the boundary wall. The cemetery was

designed by W H Cowlishaw.

Source : Commonwealth War Graves Commission .

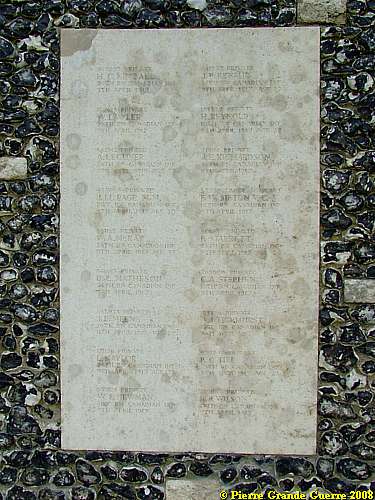

In front of the Cross of Sacrifice, on the southern wall: 3 plaques.

From left to right:

Names of Canadian soldiers, ...

... and this informative inscription:

View from the Cross of Sacrifice at the tip of Vimy Ridge. On the right stands one single headstone ...

... of Private A. Stubbs.

We leave this remarkable cemetery.

Continue

to: " Canadian National VIMY Memorial

".

Or continue

to: " CHAMPAGNE - St. Hilaire-le-Grand - Mont Navarin

"